Do you have a document or even a full-length book that you would like to enter into a computer's database or word processor? You could re-type the entire thing. If your typing ability is as bad as mine, that will be a very lengthy task. Of course, you could hire a professional typist to do the same, but that is also expensive.

We all have computers, so why not use a high-quality scanner? You will also need optical character recognition (OCR) technology.

OCR is the technology long used by libraries and government agencies to make lengthy documents available electronically. As OCR technology has improved, it has been adopted by commercial firms, including Archive CD Books USA, MyHeritage.com, FamilySearch.org, ProQuest (producers of HeritageQuest Online), Ancestry.com, Google Books, Archive.org, and many other companies.

For many purposes, OCR is the most cost-effective and speedy method available. OCR is much better and cheaper than hiring an army of clerk typists. In some cases, you may be able to have an image of a document converted to text free of charge by using OCR services “in the cloud.” OCR does, however, have drawbacks.

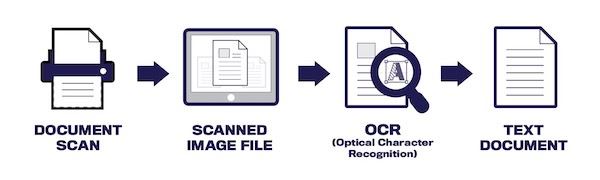

OCR is actually the second step in the conversion process. The first step is to scan the document or book in question, much the same as you would scan a photograph. The scanner converts each printed page to a bitmap file, a pattern of dots that actually comprise an electronic image of the page. Software that comes with the scanner stores the file on the computer's hard drive in TIFF, JPG, or some other image format.

Next, specialized optical character recognition (OCR) software is used to examine every word the image and convert it to text. Older OCR software would compare the individual letters in a stored image against stored bitmaps of specific fonts. These pattern-recognition systems worked well with high-quality scanned images of text that used exactly the same fonts as those expected by the software. In other words, it rarely worked. It was rare that the scanned images exactly matched the stored bitmap images of individual characters. Only a few years ago, OCR had a reputation for inaccuracy.

Today's OCR programs have added multiple algorithms of neural network technology to analyze the stroke edge, the line of discontinuity between the text characters, and the background. Allowing for irregularities of printed ink on paper, each algorithm averages the light and dark along the side of a stroke, matches it to known characters, and makes a best guess as to which character it is. The OCR software then averages or polls the results from all the algorithms to obtain a single reading.

Finally, the derived words and sentences are sent through spell checkers and syntax analyzers, which try to find any remaining characters that were decoded improperly. These analyzers check the context of the words in each sentence. The software uses its stored knowledge of parts of speech and grammar to recognize individual characters.

The results can be great for scanned English sentences. However, rows of numbers, such as stock market reports, generally do not fare well in the scanning and OCR decoding process. Neither do lists of names, such as found in telephone books, city directories, or old genealogy books.

Today, OCR software can recognize a wide variety of fonts, but handwriting and script fonts that mimic handwriting are still problematic. Nobody has yet created a commercially successful OCR product for decoding handwriting.

Technology advances have made OCR more reliable although still not perfect. Even with the best software available today, you can expect a minimum of 90% accuracy for average-quality documents. Despite vendor claims of one-button scanning, achieving 99% or greater accuracy takes clean copy and practice setting scanner parameters. It also requires you to "train" the OCR software with your documents.

Another cause of OCR inaccuracy is scanner quality. Using a $50 scanner will always result in more errors than using a higher quality scanner, regardless of the OCR software used. The quality of the scanner's charge-coupled device light arrays (the part of the scanner that detects light and dark areas of the scanned page) will affect OCR results. The more tightly packed these arrays, the finer the image and the more distinct colors the scanner can detect. Such technology costs money. Cheaper scanners have less densely packed charge-coupled device light arrays, resulting in lower-quality scans.

Smudges or background color also can fool the recognition software. Scanning a photocopy or a reprint of an old book also will create many additional errors. The human eye may think that each character is sharp and distinct, but the minute "fuzziness" of each character in a photo-reproduced page will impede the scanner's microscopic "eyes." One important outcome is that scanning an original book will always result in better OCR accuracy than scanning a reprint of the same book.

These days I am using a Raven Plus scanner and its OCR capabilities are impressive. I runs about 99% accurate if the pages being scanned are crystal-clear quality. However, that high accuracy is also reflected in the Price of the Raven Pro: about $650 at Amazon and most other online discount merchants.

To be sure, there is a cheaper version of the scanner as well. The Raven Original sells for “only” $420. However, I cannot vouch for the quality of the OCR conversion. I also know the Raven Original is slower (17 pages per minute versus 60 pages per minute for the Raven Pro).

With both versions of the Raven scanner as well as with most other brands of scanners, adjusting the scan's resolution can help refine the image and improve the recognition rate, but there are trade-offs. For example, in an image scanned at 24-bit color with 1,200 dots per inch (dpi), each of the 1,200 pixels has 24 bits' worth of color information. This scan will take longer than a lower-resolution scan and produce a larger file, but OCR accuracy will be higher.

A scan at 72 dpi will be faster and produce a smaller file — good for posting an image of the text to the Web — but the lower resolution will likely degrade OCR accuracy.

Most consumer-grade scanners are optimized for 300 dpi, but scanning at a higher number of dots per inch will increase accuracy for 6-point fonts or smaller. Most commercial OCR services scan at much higher densities than 300 dpi.

Text documents are normally scanned as bilevel (black and white only) images. Bilevel scans are faster and produce smaller files because, unlike 24-bit color scans, they require only one bit per pixel. Some scanners can also let you determine how subtle to make the color differentiation.

Which method will be more effective depends on the image being scanned. A bilevel scan of a shopworn page may yield more legible text. But if the pages to be scanned have turned to a sepia color, or if the text of an old document has faded, the OCR software will struggle to identify each letter correctly.

OCR scanning is a great convenience and will obviously reduce your need to re-type documents. However, the technology is still not perfect. Even with a high-quality scanner and today's best software, you can expect the scanning of old books to produce numerous errors. Significant manual "clean-up" will be needed.

In the “good old days” of computing, say five years ago, the only method of performing OCR conversion was to purchase OCR software and install it in your own computer. The better OCR products are expensive to purchase, consume a lot of disk space, and require (expensive) powerful personal computers, and also may require frequent upgrades. While installing software on your own computer is still possible, it is losing popularity. If you want to perform OCR scanning “the old-fashioned” way, the following products are some of the more popular options for consumer use:

Abbyy FineReader 10 Professional Edition for Windows: $199.99 at: http://finereader.abbyy.com. A free trial version is also available.

Abbyy FineReader Express Edition for Macintosh: $119.99 at https://www.abbyy.com/en-us/finereader/pro-for-mac. A free trial version is also available.

OmniPage by Nuance (now a part of Kofax): $149.99 to $499.99, depending upon the version selected, at https://www.kofax.com/Products/productivity?source=nuance

ReadIris 12 for Windows and Macintosh: $99.99 to $199, depending upon the version selected, at https://www.irislink.com/EN-US/c1810/IRIS---The-World-leader-in-OCR--PDF-and-Portable-scanner.aspx (A free trial version is available.)

SimpleOCR Freeware (limited capabilities but good for experimentation and learning): free at http://www.simpleocr.com/

The above are list prices. You may find the same products sold at discount if you shop around.

One warning: you often get what you pay for. While these products do vary somewhat, the cheaper products usually produce many more errors than do the higher-priced OCR products. It may be false economy to purchase a cheaper OCR product if you have to spend many hours "touching up" the errors. Spending a few dollars more at the beginning generally results in higher accuracy and significantly less "clean up" labor.

As the world has moved away from free-standing computers with programs installed to perform various tasks, a new technology has emerged. It is now possible to upload images of text to very high-powered computers in the cloud and have those computers perform the conversion for you. Such conversions are always cheaper that purchasing and installing OCR software when all that is needed is a few hundred documents or less. In many cases, the OCR conversion can be performed free of charge!

Free Cloud-based OCR Conversion Services

Google Drive

Google's cloud-based Drive service provides free OCR conversion to everyone (with up to five gigabytes of storage space). Drive will convert single pages or multiple pages at a time. I first created a new folder in Drive and then copied the .PNG image to that folder. I then waited about an hour. When I returned, I found I had two files in the folder:

the original .PNG file and a new file that contained the new text

Despite a bit of curling in the image of the original page, Drive did a great job of converting the image to text.

For more information about Google Drive, go to https://support.google.com/drive/answer/176692?hl=en.

My experience with the free cloud-based services was encouraging. The resulting OCR conversion was as accurate as the $500 commercial products and required no software installation and almost no disk space.

Free Online OCR

The site claims to be able to support PDF, GIF, BMP, JPEG, TIFF, and PNG as input. Outputs can either be DOC, a PDF text document, RTF, and TXT. In my brief experimenting with the site, I found the results were mediocre. If you want to convert simply-formatted documents to PDF, this is a great tool. In terms of converting to DOC the results weren’t as good as some of the other services.

You can try it for yourself at: http://free-online-ocr.com.

i2OCR

i2OCR claims to recognize more than 60 languages, can handle multi-column layouts (by removing the formatting), has no file-size limits, can convert uploaded files and from URLs. However, it is simplistic. Namely, it doesn't attempt to preserve the formatting of the original text. The output is strictly text; no paragraphs, no bold, no italics, no underlining. You can quickly correct any mistakes in the side-by-side view, before copying the text to other programs, or downloading as DOC, PDF, or HTML.

In short, you will still need to manually perform a lot of clean-up work. Check it out yourself at: http://www.i2ocr.com

Online OCR

Online OCR supports 46 different languages, and can convert PDF, JPG, BMP, TIFF, and GIF into Word, Excel, or Plain Text format. The site claims “converted documents look exactly like the original — tables, columns and graphics”. In my testing, the results usually looked "exactly like the original" although some manual clean-up was still required.

You can convert up to 15 images per hour (5-megabyte limit). The output can be saved as DOCX, XLSX, and TXT but there is no option to save as PDF.

Online OCR is available at: http://www.onlineocr.net

In short, the free online OCR tools are worth what you pay for them. They are good for an occasional effort by an individual but you won't want to use them to convert hundreds of printed books to machine-readable versions.

Summation

Whether you “do it yourself” or if you use the power of the cloud, converting images of documents to text by the use of optical character recognition is a simple method of using very complex software. With today's technology, the complexity is normally hidden for the user. Simply create an image with a scanner or a high-resolution digital camera, submit it to the online or offline software, and wait a short while for the computer to make the conversion and return text to you. The results are rarely perfect but the required manual cleanup will still be much easier than re-typing everything by hand!