The U.S. Census records for the extreme northern strip of land in Maine have been missing for more than 150 years, but now have been found. In fact, a transcription of those missing census records is even available on the World Wide Web. I found some of my ancestors listed on the Web site, more than 40 years after I first looked for them in the National Archives microfilm! (That was before the microfilms became available online.)

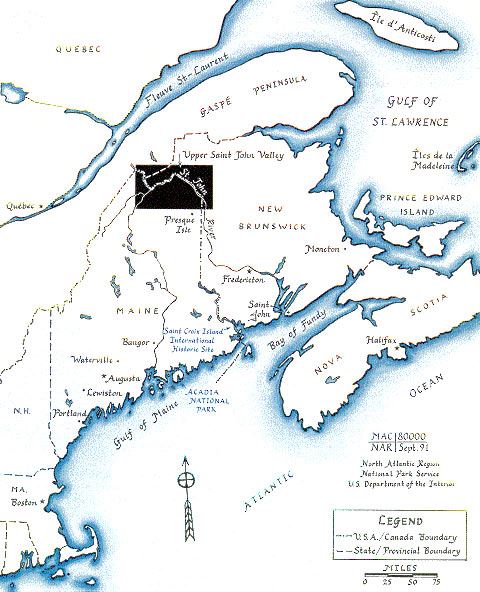

In 1820, the land of the Saint John River Valley in what is now Maine and New Brunswick was disputed territory, claimed by both the United States and Great Britain. A government official, such as an American census enumerator, could be arrested and incarcerated by the British authorities if he dared to enter this disputed territory. Likewise, British authorities who entered the disputed land also were in danger of arrest and even imprisonment.

When I found the towns were not listed in the 1820 U.S. census records on National Archives microfilm no. M33, reel no. 38, I assumed that the census takers (enumerators) never set foot in the disputed territory. It seems that I was wrong.

When looking at the same microfilm, Chip Gagnon noticed that, at the end of those same records, enumerator True Bradbury listed the total number of people in each of the towns in the Upper Saint John River Valley, including even those towns missing on the microfilm copy. If Mr. Bradbury knew exactly how many people lived there, Chip realized, then he must have visited each household and recorded the information. So, what happened to his hand-written records?

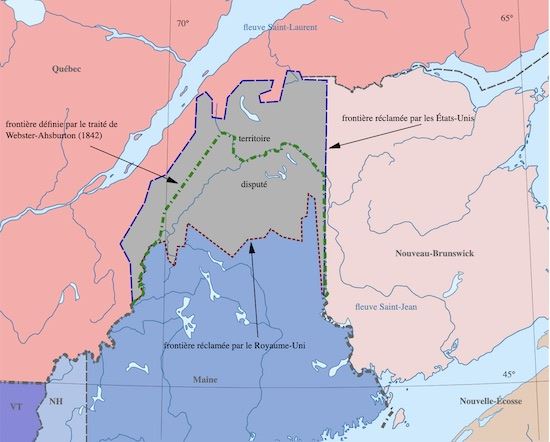

As explained on Chip’s Web site, one must consider the history of the area in 1820 and about twenty years thereafter. This disputed land was a cause of much difficulty and many negotiations between the governments of the United States and Great Britain. Remember, too, that this was only a few years after the War of 1812; these two governments still maintained an adversarial relationship. Eventually, the King of the Netherlands arbitrated a decision that determined the exact boundary between the United States and Canada in 1831. Following on this decision, the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty finally settled the border between Maine and New Brunswick without bloodshed.

THE GREEN BROKEN LINE SHOWS THE RESULTS OF THE WEBSTER-ASHBURTON TREATY.

As part of the process of determining the boundary, someone apparently decided to document how many people were involved in this land dispute. After all, citizenship and property were involved. The only records of the residents were those of the U.S. census. It appears that the census records of the Saint John River Valley were separated from the rest of the census records, probably in 1828, to be used as part of the arbitration process. Apparently, the records were never returned to the original repository.

As Chip Gagnon states on his Web site:

“I recently went to Washington DC to look for the original returns in the National Archives. I searched through the records of the State Department related to the border dispute. In the documents related to that dispute I found the handwritten manuscript copy of the published document that I cite below. Included was the copy of returns for Madawaska, New Limerick and Houlton. The copy was made in 1828 by the Clerk of the US Court for the District of Maine (where the 1820 census returns were deposited). This copy was then sent to Washington for inclusion in the documentation being prepared for submission to the arbitrator.

“The document is a handwritten copy made from the original and certified as such. I have included the text of the certification at the end of the transcription of Madawaska. What we learn from this certification is that an original copy of the returns was present in the District Court of Maine as late as 1828. But we also learn that the State Department did not have the original version of the census returns, relying rather on this copy. I would also hazard to guess that the British government too had requested a copy of these returns in its preparation for its own arguments on the border.

“Given these facts, it seems probable that when the returns were pulled in 1828 in order to make a copy for the arbitration document, they were not returned to their original place. Thus when the returns were all sent to Washington, the Madawaska, Houlton and New Limerick returns were not included. The question remains, however, whether they are somewhere in Maine. I am currently trying to determine that fact.”

NOTE: The records Chip Gagnon refers to are for the towns of Madawaska, New Limerick and Houlton. However, those three townships covered many square miles in 1820. They have since been subdivided many times, and new towns formed. These records cover what now comprises several more towns in the Upper Saint John River Valley.

Not only are U.S. towns covered, but even several communities now in Canada were enumerated. In some cases, these may be the only census records of those Canadian towns at any time before 1851. Not many of us would think to look for residents of Canadian towns in “missing” U.S. census records.

I was delighted when I learned of Chip Gagnon’s hard work. His published listing contained the names of several of my ancestors that had not been listed in the U.S. census.

Much more information is available on Chip Gagnon’s website, including his transcriptions. You can find his excellent site at: http://www.upperstjohn.com/ and especially (in English and in French) at http://www.upperstjohn.com/1820.