From the 1850s through the 1920s, New York City was teeming with tens of thousands of homeless and orphaned children. To survive, these so-called "street urchins" resorted to begging, stealing, or forming gangs to commit violence. Some children worked in factories and slept in doorways or flophouses. The children roamed the streets and slums with little or no hope of a successful future. Their numbers were stunningly large; an estimated 30,000 children were homeless in New York City in the 1850s.

Charles Loring Brace, the founder of The Children's Aid Society, believed that there was a way to change the futures of these children. By removing youngsters from the poverty and debauchery of the city streets and placing them in morally upright farm families, he thought they would have a chance to escape a lifetime of suffering.

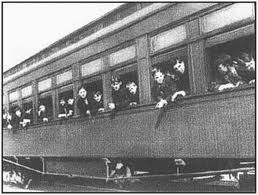

Brace proposed that these children be sent by train to live and work on farms out west. They would be placed in homes for free, but they would serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores around the farm. They wouldn't be indentured. In fact, older children placed by The Children's Aid Society were to be paid for their labors.

The Orphan Train Movement lasted from 1853 to the 1920s, placing more than 120,000 children. Most of these children survived into adulthood, married, and had children of their own. Several million Americans today can find former Orphan Train children in their family trees.

Orphan Trains stopped at more than 45 states across the country, as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children. There were numerous agencies nationwide that placed children on trains to go to foster homes. In New York, besides Children's Aid, other agencies that placed children included Children's Village (then known as the New York Juvenile Asylum), what is now New York Foundling Hospital, and the former Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York, which is now the Graham-Windham Home for Children. Not all the children were from New York City. Children from Albany and other cities in New York state were transported, as were some from Boston, Massachusetts, where the Boston Children's Services merged with the New England Home For Little Wanderers, which also is still active today.

Orphan Trains stopped at more than 45 states across the country, as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children. There were numerous agencies nationwide that placed children on trains to go to foster homes. In New York, besides Children's Aid, other agencies that placed children included Children's Village (then known as the New York Juvenile Asylum), what is now New York Foundling Hospital, and the former Orphan Asylum Society of the City of New York, which is now the Graham-Windham Home for Children. Not all the children were from New York City. Children from Albany and other cities in New York state were transported, as were some from Boston, Massachusetts, where the Boston Children's Services merged with the New England Home For Little Wanderers, which also is still active today.

Only a few of the Orphan Train children are alive today, and most were too young at the time to remember their experiences. However, a few elderly Americans can recall their experiences on the Orphan Trains.

Stanley Cornell and his brother are amongst the last generation of Orphan Train riders. When asked about his experience, Mr. Cornell replied, "We'd pull into a train station, stand outside the coaches dressed in our best clothes. People would inspect us like cattle farmers. And if they didn't choose you, you'd get back on the train and do it all over again at the next stop."

Cornell and his brother were "placed out" twice with their aunts in Pennsylvania and Coffeyville, Kansas. Unfortunately, these placements didn't last, and they were returned to the Children's Aid Society.

"Then they made up another train. Sent us out West. A hundred-fifty kids on a train to Wellington, Texas," Cornell recalls. "That's where Dad happened to be in town that day."

Each time an Orphan Train was sent out, adoption ads appeared in local papers before the arrival of the children.

J.L. Deger, a 45-year-old farmer, knew he wanted a boy, even though he already had two daughters, ages 10 and 13.

"He'd just bought a Model T. Mr. Deger looked those boys over. We were the last boys holding hands in a blizzard, December 10, 1926," Cornell remembers. He says that day he and his brother stood in a hotel lobby.

"He asked us if we wanted to move out to farm with chickens, pigs, and a room all to your own. He only wanted to take one of us, decided to take both of us."

Life on the farm was hard work.

"I did have to work and I expected it, because they fed me, clothed me, loved me. We had a good home. I'm very grateful. Always have been, always will be."

Cornell eventually got married. He and his wife, Earleen, now live in Pueblo, Colorado. His brother, Victor Cornell, a retired movie theater chain owner, is also alive and living in Moscow, Idaho.

Stanley Cornell believes he and his brother are two of only 15 surviving Orphan Train children.

Some of the children struggled in their newfound surroundings, while many others went on to lead simple, very normal lives, raising their families and working towards the American dream. Although records weren't always well kept, some of the children placed in the West went on to great successes. There were two governors, one congressman, one sheriff, two district attorneys, and three county commissioners, as well as numerous bankers, lawyers, physicians, journalists, ministers, teachers, and businessmen.

The Orphan Train Movement and the success of other children's aid initiatives led to a host of child welfare reforms, including child labor laws, adoption and foster care services, public education, and the provision of health care and nutrition and vocational training.

The Orphan Train Heritage Society of America in Concordia, Kansas, serves as a clearinghouse of information about the estimated 150,000 children who were "placed out" from 1854 to 1929. It helps members establish and maintain family contacts, retrace their roots, and preserve the history of the Orphan Train Movement. Look at https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/orphan-train-heritage-society-of-america-inc-2400/ and at http://orphantraindepot.org/ for more information.

Other web sites that provide information about America's Orphan Trains may be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orphan_Train, and at https://www.childrensaidnyc.org/about/orphan-train-movement.